Breathing is something we all do on a daily basis, that we tend to overlook. Most of us are not conscious of our breathing patterns and habits since our bodies do the work for us, whether we’re sitting, standing, sleeping, or anything in between. Proper breathing is actually one of easiest habits we can focus on that has a high impact on our posture and physiology.

Anatomy of breathing

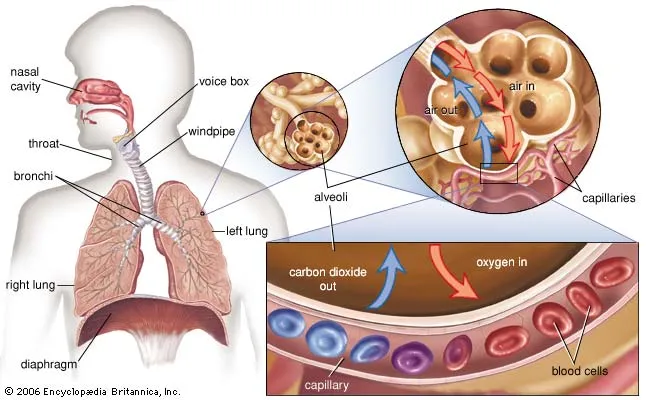

Breathing involves two main processes – inspiration, where air moves into the lungs, and expiration, where air leaves the lungs. When we properly inhale with our nose (instead of our mouth ;), air travels inward into the lungs as our diaphragm allows our lungs to expand and our intercostal muscles allow our ribs to move up and outwards. When we exhale, our intercostal muscles and diaphragm relax, essentially squeezing the air out of our lungs. Why should we care about these two muscles? For starters, the diaphragm is an important posture stabilizer, connecting your rib cage to your spine and ensuring it stays upright. The intercostal muscles also contribute to supporting and stabilizing the rib cage and thoracic spine in three dimensional movements.

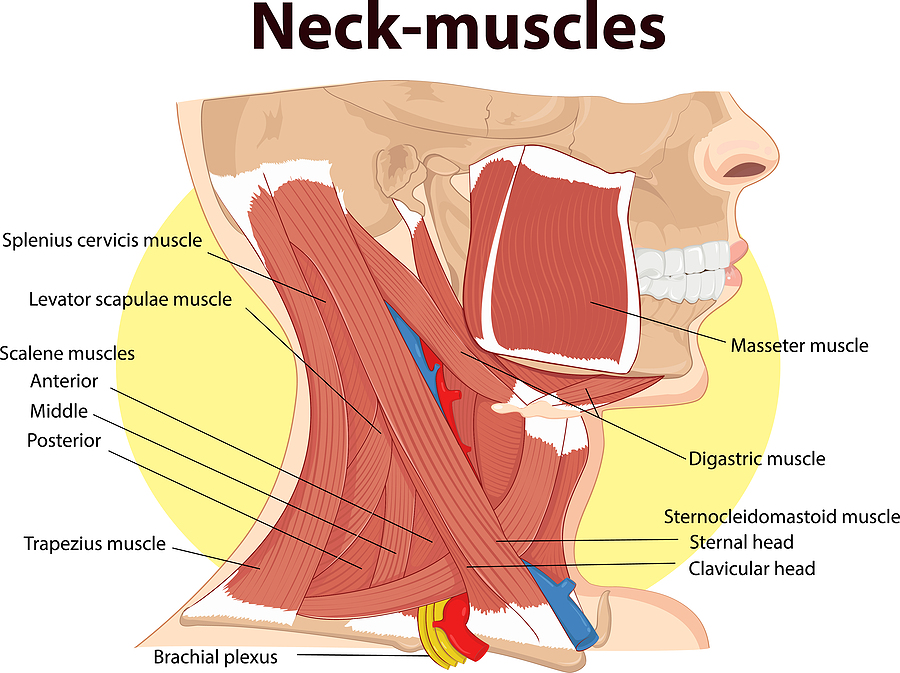

The symphony of these muscles in the breathing processes contributes to proper positioning of not just the thoracic spine and rib cage, but also the scapulae and the cervical spine/neck (preventing exacerbated forward head posture!). Using the wrong muscles to breathe, or not fully engaging the right muscles, creates chronic tension that is impossible to stretch out. In instances of weakness or illness, the muscles in your neck can and do help you breathe (the sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius, and scalene) by compensating for diaphragm weakness.

Metabolism of breathing

Respiration, as a physiological process, refers to the inhalation + utilization of oxygen, and creation + exhalation of carbon dioxide by our bodies. Oxygen is required by all of our body’s cells to carry out the metabolic processes needed to sustain life; carbon dioxide is a byproduct of these processes, and contributes to blood acidity if not buffered or removed.

Although the gas exchange of respiration takes place within the alveoli of our lungs, this biochemical process is controlled by our Central Nervous System, particularly the brainstem. The brainstem relies on nerve signaling to adjust ventilation levels based on arterial CO2 levels, and is capable of recruiting the diaphragm and thoracic muscles to breathe without any conscious effort on our behalf. As a result, if you already have a sub-optimal breathing pattern and it “works”, your body won’t bother change anything.

Research studies investigating the impact of deep breathing at a molecular level are being conducted, but it’s evident that mouth breathing doesn’t help your metabolism as much as diaphragmatic/deep breathing does. In a study conducted by medical researchers at NYMC, Columbia, and Cornell, it was found that diaphragmatic breathing significantly decreased the levels of C-reactive protein in patients with IBD; C-reactive proteins are molecular markers that increase with inflammation. Another study performed by Ma. et. al in 2017’s “The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults” showed significantly lower cortisol (a molecular marker for stress) levels in groups that performed diaphragmatic breathing when compared to a control group that explicitly didn’t.

Postural Roadblocks From Poor Breathing Patterns

If you build a house upon a weak foundation, it will not be as durable and strong as it could be – this applies to our bodies as well. Poor breathing patterns limit activation of deep abdominal musculature, which translates outwards to impaired posture, in the hip complex and above our chest. Effectively, this translates into tight abs, upper cross syndrome and forward head posture (check out our article here), tight hip flexors, and reduced lung volume and breathing rates.

Medical researchers have done research on this topic, and some studies I found interesting are summarized below:

- Okuru et. al evaluated the exercise tolerance of children between 2010-2011, examining the relationship between forward head posture comparing nasal and mouth-breathing children. Mouth-breathing showed a significantly negative impact on respiratory biomechanics and exercise capacity, and it was in these kids that forward head posture was prevalent as the body’s means to compensate and improve respiratory function.

- Clavel et. al studied patients with obstructive sleep apnea and compared their posture and spinal alignment with healthy individuals. Their results showed that the sleep apnea patients displayed higher instances of kyphosis and forward head posture, as well as increased postural disturbance of respiratory origin (lack of diaphragm engagement). This shows that posture and proper breathing have significant implications on sleep quality.

- Zaccaro et. al conducted a systematic review on medical literature to examine the impact of deep breathing on psycho-physiological mechanisms in the human body. Their findings showed an increase in cognitive function, higher emotional control, and increased psychological well being in individuals who were deep breathers, compared to those who used their mouths.

What now?

So now we’ve established a baseline that mouth breathing is not an optimal way to breathe when compared to nasal breathing. How are we supposed to fix this, and maintain optimal heath going forward? Here’s how to breathe deeply, and engage all of the relevant musculature:

- Relax your neck and shoulders, and raise your chest

- Breathe in slowly through your nose

- Bring air deep into your belly as it expands, imagine your diaphragm pulling downwards

- Hold the breath for a few seconds, pay attention to the involvement of your spine, ribs, and pelvis

- Exhale. Rinse and repeat.

Breathe deeply and properly folks. It’s better for your posture, and overall well-being.

Additional References

https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/23/health/breathing-pain-relief-posture-movement-wellness/index.html

Leave a Reply